Reflections on Genocide

Casco Bay High School and University of Southern Maine

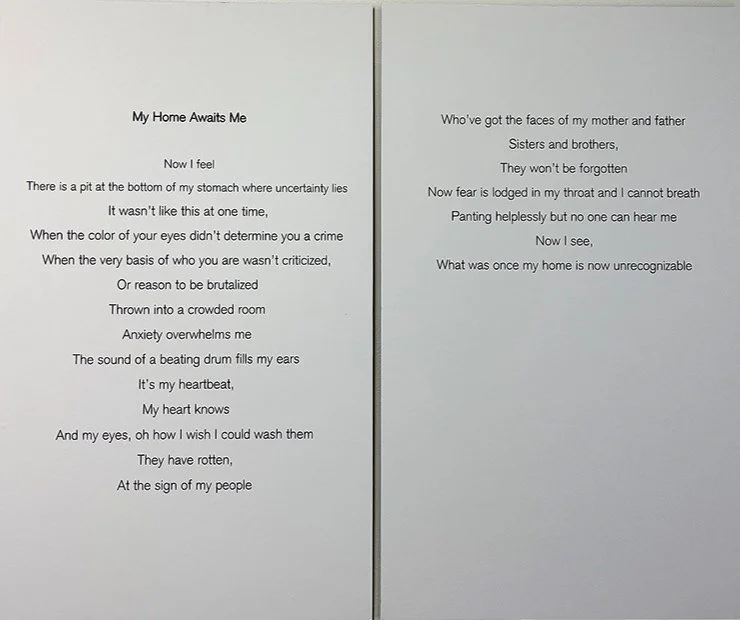

My Home Awaits Me

By Farhiya Abukar, Casco Bay High School Class of 2023

Written word on paper and foam board

This piece is a poem about the genocide towards the Isaaq Clan in Somaliland. The genocide started with the Somali leader Siad Barre who was against the Issaq tribe fighting for their independence. Somaliland became known as a country when he was overthrown in 1991.

This poem connects to the Holocaust because the genocide in Somaliland was targeted towards a specific group of people. Those who were some opposed to his way of ruling would be kidnapped and brought to the Valley of Death. More than 40,000 people were killed and more than 300,000 civilians fled. The capital city, Hargeisa was also being destroyed in the process. This genocide has led to the ongoing conflict between the Landers and the Somali people. Even though many years have passed, they are uncovering new bodies everyday all over the country.

This genocide is not one that is heard about often and with this piece, I hope for people to consider that there have been multiple genocides. The Holocaust was a horrible genocide. However, the Somaliland genocide is also worth learning about because we are not in a position to be judging which genocide was worse than the other, only to equally hear people's stories who experience such a crime regardless of who they are.

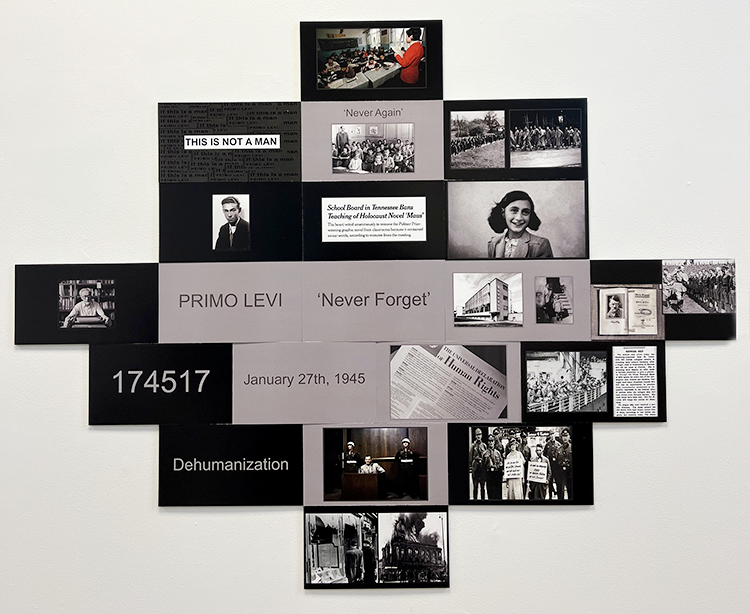

This is Not a Man

By Haley Allen, Casco Bay High School Class of 2022

Compilation of photographs from WWII and post war

I built this piece surrounding the theme of dehumanization seen in the Holocaust. While there were many ways in which Jewish prisoners were dehumanized, I highlighted the strategies that clearly stood out in my learning of the history before, during and after the Holocaust. These are: public degradation, public humiliation, and isolation. I incorporated these themes into my art by reflecting examples on my slides while speaking of each aspect.

For the dehumanizing strategy of public degradation, I used examples from Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), a night during which Germans publicly degraded Jews by destroying synagogues and Jewish businesses. This event enforced the negative image that Jewish citizens were already enduring. For public humiliation, I used ‘Race Defilement’ to illustrate the ways in which it dehumanized Jews. Race Defilement was the term used when Aryans had relations with someone of the Jewish race. Finally, for isolation, I used the example of Cuba refusing to allow Jewish refugees into the country for safety. A group of Jewish refugees, fleeing persecution in Germany, sailed on the St. Louis to Cuba and were denied entry, sending them right back to the terrors of what was previously their home.

The degree to which dehumanization stripped entire lifetimes away from Jewish prisoners is extremely intense. I wanted to represent this intensity in my piece, so the slides also represent what the life of a Jew during this period might consist of. These images are moments when they were forced to endure; these stories convey what they were there to witness. Jews endured the content of these images daily. I also wanted this piece to express how dark their lives were, with no hope, nothing to look forward to. You can see the despair in the color scheme: dark gray is used up until the Bauhaus and Gertruda Bablinska slide, where it transforms to a lighter color. I did this purposefully, to signify a change in the darkness, a mark of some hope that Jewish prisoners could finally grab onto. The title, a play on Primo Levi’s If This Was a Man, is intended to describe that the ways in which Jewish prisoners lived were unnatural at the least and should never be excused, as there is nothing in the world that can excuse that treatment. I chose to write a poem because I felt that this form of condensed writing was the best way to express the dehumanization of Jews during the Holocaust. The pictures are there to support what I am saying, and to provide examples of the content, but the poem is written for a deeper explanation of what truly was going on. Dehumanization was the essential strategy that the Nazi party utilized in an attempt to get Jews exactly where they wanted them, both mentally and physically. Decades of dehumanization followed liberation, while prisoners attempted to learn how to exist in such a state of trauma. My hope for this piece is that it causes people to continue to acknowledge the severity of the mental torture that Jews experienced during the Holocaust.

Agnes and Her Mother

By Quinn Bolster, Casco Bay High School Class of 2024

Acrylic on canvas

This is a painting of Agnes Gertrude Wohl (maiden name Mendelovits) and her mother. The focal point of the painting is the portrait because the goal of the piece is to recognize the humanity of both the Mendelovits, and every person affected by genocide. Providing faces to the massive numbers given when discussing the Holocaust, and other genocides, is a way to combat the dehumanization persecutors tried so hard to cultivate.

This portrait is based on a picture that was taken for false identification, and was the last picture taken of Agnes and her mother. Using an image taken in such terrible circumstances is a way to show how humanity can serve to change the narrative. Nazis aimed to destroy Jewish life completely, so reusing an image that used to represent fear to instead represent humanity can disrupt this destruction.

In 1944, Agnes was forced into an overpopulated Hungarian ghetto. Shortly thereafter, her family went through a terrifying and rapid change in environment, being forced to live in a basement with 60 other people. In January of 1945, the Nazis in Hungary found this basement, and Agnes and her mother were forced into a Nazi headquarters. The war would end the following September, and the Nazis had begun trying to kill as many Jewish people as possible out of desperation. Soon after being moved to Nazi headquarters, the Nazis killed Agnes’ mother. Agnes escaped after being shot in the shoulder and was able to reunite with her father and brother later. Agnes was 11 years old.

The background of the piece represents the chaos Agnes experienced, and each single design represents a facet of her story. The way Agnes highlighted small moments in her story was striking, and to illustrate that I created contrast between a dark background and lighter colors. For instance, Agnes’ grandmother baked her family bread before they were forced out of the ghetto. The bright orange and yellow surrounding Agnes and her mother represent this bread, and the joy it provided in a dark time.

I was particularly drawn to Agnes’ story due to the shocking nature, but also due to the loss of her mother. I was able to empathize with this specific portion of the story, which helped me realize my greatest takeaway from studying genocide: genocides are not as far as they may seem. Being able to connect to something that had seemed so long ago, has helped me understand the importance of learning from the Holocaust. Once we understand what we can learn from past genocides, we will be able to prevent current and future genocide. Just under 2 months ago, a genocide was declared in Myanmar. Genocide is not a thing of the past, and we must learn from the horrific tragedy that is Holocaust.

Our Collective World

By Andrew Box, Casco Bay High School Class of 2025

Paper mache, black spray paint, black and gold sharpies, acrylic paint, foam pipe wrap, poly matte sealer, a mirror and a globe stand

This globe is the world, a small replica of our planet we inhabit. When looking at a globe, all I can see is the painful red wounds left from the slaughter of people during genocides. My art piece shows the unrest these genocides have brought. The color black is a void, a place that can consist of anything or everything covered by darkness. Red represents the sharp daggers that seize your attention. These are the spots where meaning lies. In the art piece in front of you, these red markers are where genocides have occurred. Genocides are the worst of human nature, the moment where we are devalued and murdered by others. However, within these red points in our history are the yellow marks of resistance. Victims’ resistance against perpetrators’ discrimination and dehumanization shows the fight for equality among all humankind. This resistance against oppressors is incredibly important to acknowledge because it shows how people will risk anything to acquire freedom. When you see yourself in the mirror, it is my hope that you will see yourself as part of that resistance.

The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states: “Disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom.”

Acknowledged in this passage of the UDHR is the fact that all human beings deserve to be free, and that this freedom has been challenged by genocides. The large impact of these genocides on humanity can be best seen through examples. The Holocaust is a focal point of human history, showing the atrocities that can happen if people don’t step up. The Nazi party used anti-Semitism to gain power and strength within Germany. From these roots of racism, came ghettos and extermination camps, taking humanity away from people and enacting mass murder. During the Holocaust, while Jews were being discriminated against and segregated, the people in Germany and the powers outside of Germany ignored this infringement of human rights. In fact, the reason the Allied powers went to war was because of the German invasion of Poland, not the mistreatment and slaughter of Jewish people.

What my artwork is primarily pointing out is the responsibility that we all have to combat these genocides. Our lack of interference when unspeakable events like this happen allows perpetrators to gain power. For example, the Rwandan genocide of 1994 was broadcast as international news, yet had little opposition from outside groups. If we had done more, we could have prevented a genocide. It is the citizens’ collective responsibility to get our governments involved. The press and public support have clearly contributed to the US government’s decision to send aid to Ukraine. We, as citizens, need to recognize our power to make a difference. That is the reason there is a mirror in the globe: to signify your part in the battle against genocides.

Before My Eyes

By Olivia Chong, Casco Bay High School Class of 2024

Tulle, watercolors, sharpie, thread, tissue paper, wire and plastic

This sculpture represents the concept of bearing witness to dehumanization and violent systematic oppression. This piece is designed to be interactive to invite the viewer into an immersive experience.

The images portrayed in the fabric with a muddied color palette, are representative of experiences and places of oppression recounted in Primo Levi’s book, If This Is A Man. The three panels represent the three ways to be a witness: victim, perpetrator, and passive bystander. I hope to demonstrate these three perspectives through my piece. The eyes can be interpreted as the eyes that looked the other way and did nothing. The eyes that saw and did nothing. The eyes that saw and could do nothing. The message of this piece represents the way the world was stuck in horrified shock, watching the atrocities committed by the Nazis. The nature of the veil represents how victims endured extreme dehumanization and violence, forcing many to lose their sense of being a human. The smoke represents both the crematorium, through which the Nazis hid their crimes, and the veil of uncertainty leaving the Jewish captives to stay confused and uninformed. The drawn figures depict the Auschwitz death march and represent the perpetrators’ complete disregard for human life. In 1945, the Nazis knew the war was coming to its end and took tens of thousands of prisoners from the labor camps. They then forced them to march from camp to camp, enlisting more people in these marches, and killing whoever couldn't keep up.

15,000 people in the Auschwitz death march died, 25% of the total population. The massive numbers are reflected in my art to place into perspective the horrors that were committed by the Nazi regime, and how the world stood by for far too long. In 1939, the S.S. St. Louis departed from Germany, intending to bring 937 Jews seeking refuge in Palestine or the Americas, and eventually, Cuba. However, they were turned away due to invalid papers and forced to return to Europe, where they were again placed under Nazi rule. Of the passengers, 254 were killed during the Holocaust–deaths that could have been avoided if witnesses had not become passive bystanders. This event inspired me because of the blatant neglect and abuse of people in need. How could the international community stand by and do nothing, and watch the horror unfold, serving only to witness and bystander? I hope that this piece serves as a reminder to act against oppression and totalitarian regimes, to never again be stuck in the role of witness, and to never replicate the past.

Paper Flowers

By Simone Daranyi, Casco Bay High School Class of 2022

Plywood, acrylic paint, copper wire, barbed wire, hot glue, notebook paper, and food coloring

This sculpture represents growth and beauty as a symbol of resistance and strength through the Holocaust and other genocides. Even in harsh and inhumane conditions, the beautiful paper flowers push through the ground and grow into colorful blossoms. Flowers are a way of memorializing people, and more specifically in this piece, memorializing the people who perished in the Holocaust. The paper butterfly in the piece is a reoccurring symbol in art from the Holocaust. The returning butterfly symbolizes the restoration of hope and humanity.

Flowers intertwined with the barbed wire are symbols of the Nazi oppressors. In addition, all the wire flowers are uniform and similar to the sunflowers in the book The Sunflower by Simon Wiesenthal, where in a Nazi cemetery every soldier is represented by an identical sunflower. Wiesenthal did not think that he would be memorialized in any way, writing, “For me there would be no sunflower…No sunflower would ever bring light into my darkness, and no butterflies would dance above my dreadful tomb” (Wiesenthal, 14-15). My piece acts as a memorial to Jewish people in the Holocaust like Wiesenthal who did not think they would be memorialized. The flowers are different and are made up of many colors to show that people struggled to remain individuals and maintain their uniqueness and humanity. While the gray metal looks withered and wilted, the colorful paper flowers are vibrant and alive even though they are surrounded by their oppressors.

The paper was dyed and then heated over a stovetop to dry, which reminded me of some of the processes that The Paris Forger used when he created false documents to help Jewish people escape Nazi occupied territory in WWII. Adolfo Kaminsky contributed to the fight against Jewish persecution, also known as The Paris Forger. Kaminsky created false documents to help persecuted Jewish people to escape Nazi controlled territory. When asked about his work, he stated, “Of course everything I did was illegal… but when something legal is completely against humanity… You have to fight” (Adolfo Kaminsky, 0:16). The false documents Kaminsky created saved hundreds of people.

Genocides happening around the world and throughout history are often minimized, forgotten, or even denied. There is a need for more recognition and memorialization of the people affected, displaced, and murdered in genocides, as a first step to make reparations for damage done. One memorial that stands out to me is the New England Holocaust Memorial in Boston. The memorial is made up of six large glass towers representing the six million Jewish people who were murdered in the Holocaust. Engraved on the towers are the numbers those people were assigned in concentration camps and ghettos. The memorial is effective in that it shows the sheer number of people killed, but also recognizes that each of those people was an individual.

During the Holocaust, many Jewish people lost their names and were reduced to numbers as a way of dissolving a piece of their humanity, but when all of these numbers are collectively memorialized, this destructive strategy is flipped on its head and the numbers are given new meaning of remembrance. In my piece, I decided to include six flowers to represent the six million Jewish people lost in the Holocaust. Another memorial that inspired my piece was the White Rose Pavement Memorial in Munich, Germany. The memorial is made of bronze version of the pamphlets the Scholl siblings and other students and members of the white rose would hand out and scatter to spread information and truth about the Holocaust. The paper pieces pasted on the bottom of the sculpture are laid out in a similar way to those in the White Rose Memorial.

Overall, this sculpture conveys the importance of recognition, memorialization, and remembrance as a way of continuing the resistance against the dehumanization that occurs during genocides. When individuals are recognized as people, they retain their humanity and their humanity can be honored through art. Around the world there are many memorials honoring genocides like the Holocaust: Yad Vashem in Israel, the New England and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in the US, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland, and many others. This piece is my contribution to that important artistic work.

Where There is Death, There is Life

By Maggie Ellis, Casco Bay High School Class of 2023

Air-dry clay, acrylic paint, and painted artificial flowers

I created my sculptural piece to act as a memorial for the victims of the Holocaust. My sculpture depicts a dead victim of the Holocaust lying down, with flowers growing from his chest. This depiction has a couple of interpretations that I attribute to it: the first being that the flowers are representative of the resilience and perseverance of the victims. Though many lives were lost or changed forever because of the Holocaust, many people continued to live and thrive. Though the man is dead, this is not necessarily an end. I wanted to create a piece that shows these people, and these spirits, will always remain present in a sense. I wanted to emphasis that not everything was taken from these people by the Nazis.

Additionally, the sculpture represents the idea that we cannot view the Holocaust as something in the past. This line of thinking can only breed susceptibility. Events like the Holocaust can happen again, and we have to remember that these ideals and even practices continue on. In this interpretation, the flowers represent the idea that though this particular genocide was in the past, ideals originating from this time continue to exist.

This piece was partially inspired by the poem The Wasteland by T. S. Elliot, where the phrase “April is the Cruelest Month” was used to describe the time in which the ground thawed after the winter and all the dead bodies who had been previously killed became visible. My piece incorporates a similar idea of bodies being returned back to the earth, and nature.

Additionally, I was inspired by the book The Sunflower by Simon Wiesenthal. In this book, the author notices, and grapples with the fact that Sunflowers were placed on the graves of Nazis who had passed. He questions why the dead Jewish people are not given sunflowers. I incorporated this connection drawn between flowers and death into my sculpture.

Memento

By Ahmednoor Hassan, Casco Bay High School Class of 2023

Cardboard, paper and excerpts from primary sources

My art piece is called “Memento” and it’s a sculpture to memorialize victims of Nazi violence.

The first person I am remembering is a man named Elie Wiesel. When he was 15 years old, he was taken to the concentration camp and witnessed unthinkable and unspeakable things being done to other people. He watched countless people die and had his humanity ripped right from him. He was eventually freed from this literal hell and wanted to tell his story to others, so he wrote a book called Night in 1955 to showcase firsthand the pain and suffering Jews faced in the Holocaust.

I am also memorializing Sophie and Hans Scholl, both members of a group called “The White Rose.” These incredible people saw the unfairness and the awful things being done to Jews and decided to do something about it. They posted papers of the truth in hopes people would read what actually was happening and they did. People slowly realized the truth because of them.

The third person I've decided to memorize is Anne Frank. Anne was a young girl during the Nazi party’s reign and was forced into hiding because of them. She was given a journal and all throughout her time spent hiding she would write about her experiences. Her diary was found later on and eventually made into a book so her story could be remembered.

The last person I'm memorizing is Adolfo Kaminsky, also known as the forger. This was a man spent his time trying to save lives during the Holocaust. He made fake documents every day all to save lives. If he was caught, he would have been killed but despite the risk he strived to save lives. Adolfo Kaminsky will forever be remembered as a hero.

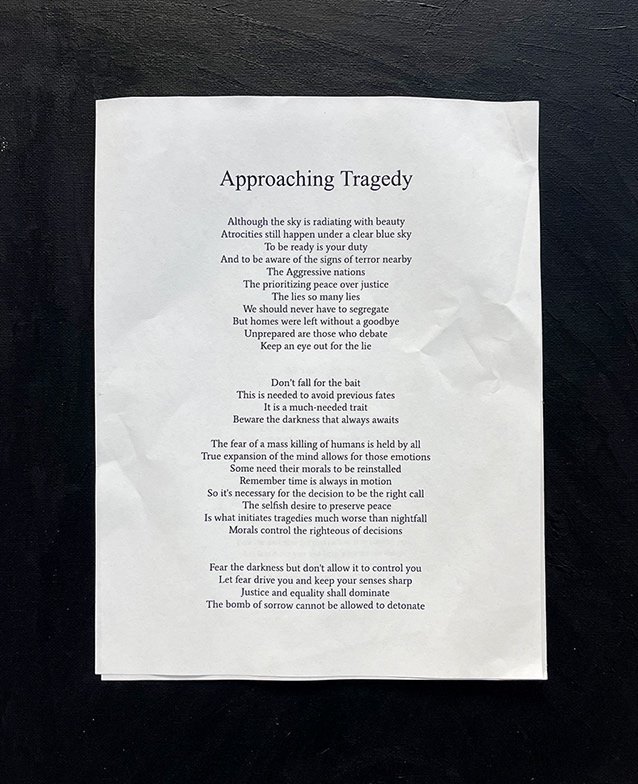

Approaching Tragedy

By Mohamedamin Mohamed, Casco Bay High School, Class of 2023

Acrylic on canvas

My piece talks about genocide prevention. It represents the ever-present danger. It uses the darkness around the poem to show that danger is always lurking. This piece is meant to convey the need to be alert. The poem is a warning about the impending darkness of genocide. It is about genocide prevention. I used the history I learned, and I picked up key points where something should have been done to prevent or curtail the Holocaust. I emphasize those moments by giving signs to look out for. These signs happened in the past and also today: like aggressive nations taking land, or the world prioritizing peace over justice. I also restricted the darkness from touching the poem to represent how there is still light, to show there are steps we can take to prevent genocide. A story that inspired this poem was about a survivor of the genocide in Cambodia. “The Khmer Rouge ordered us to leave the city ‘for three hours only’ and to carry nothing with us... I left my house with my mother, my two daughters, three sisters, and two brothers… five hours passed, one day, two days, three days…. We realized by now that this was a trip without return” (Var Ashe Houston). This story inspired me to choose to bring awareness to the lurking danger. The idea of someone's life being completely uprooted in less than four hours is horrifying. The piece is made to inform and bring awareness. Even now this is needed. Genocide is still happening, and we are still not yet armed with the resolve and insight we need to handle it.

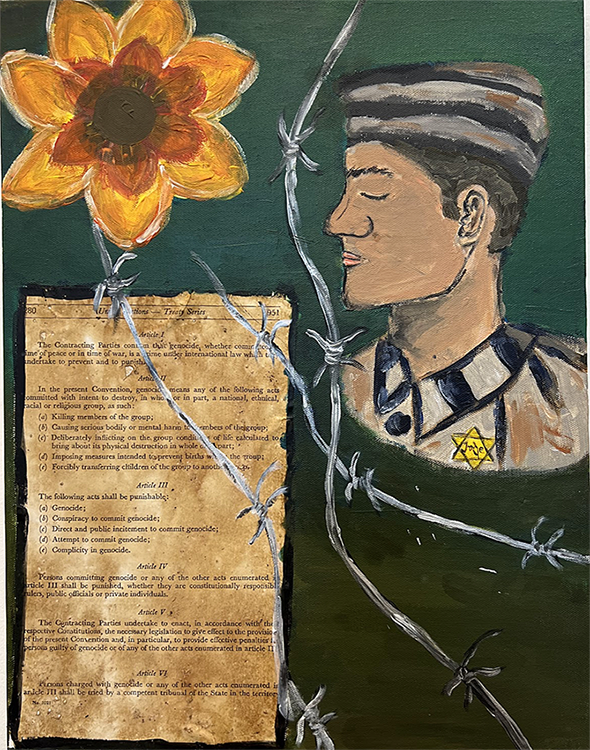

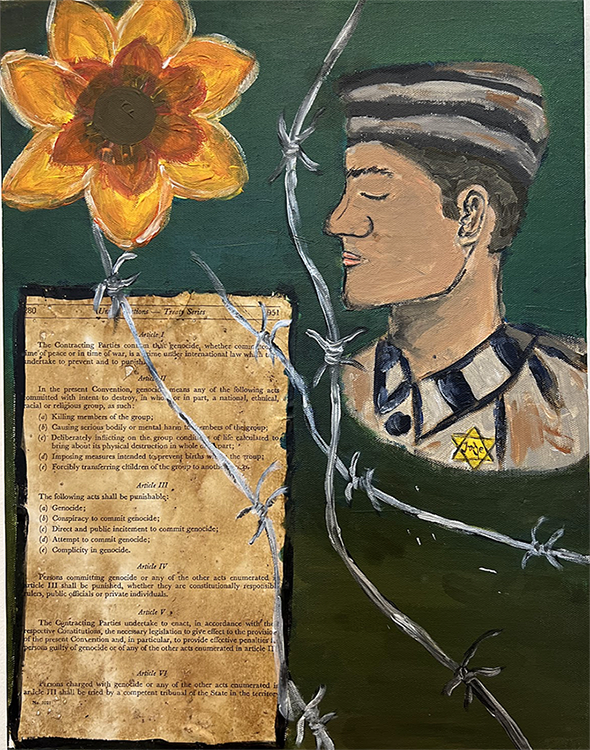

Definitions Of Light

By Fiona Nichols, Casco Bay High School Class of 2025

Acrylic and paper on canvas, 2022

This painting represents the oppression during the Holocaust and then the outcome after the Holocaust ended. The man on the right side of the painting is depicted as a prisoner in a concentration camp. He has the yellow Jewish star pinned to identify him. He is trapped behind barbed wire, without freedom of speech, and stripped of humanity. The sunflower on the left-hand corner of the painting demonstrates how a sunflower was planted above German soldiers' graves. I wanted to show how these German soldiers were given, even in death, a memorial of a flower, and how the Jewish prisoners were buried in mass graves. Clearly, German life was valued much more than a Jewish life, for Jewish people were dehumanized to the point that even in death they were treated like animals. I also wanted to share an aspect of hope in the painting, so I put the United Nations’ definition of genocide to show what came out of the Holocaust, to help prevent a genocide like this from ever happening again. The definition is also sliced with barbed wire, for even though effort has been made, many genocides have occurred since the UN definition of genocide was written. The prisoner is still separated from the definition of Genocide to show that the definition came after his oppression.

Although there was extreme oppression during the Holocaust, there were also many people who resisted. One example of resistance was a group of anti-Nazi writers who called themselves the White Rose. The group was made up of five students named Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Sophie Scholl. They created anti-Nazi leaflets to spread awareness to the public as to what was going on in concentration camps. They knew if they were caught, they would likely die. They were arrested by the Gestapo in 1943, their resistance coming to an end, however, the changes they made live on. In my painting, I show a man with barbed wire running around his face; although he's a prisoner, he also represents others silenced for speaking against Nazi policies and silenced because of who they are. The White Rose dared to speak up against the Holocaust, but they too were silenced, which is a theme in my art, where barbed wire separates the man from his right to speech and freedom.

This painting is meant to show the oppression of the past while also shedding a light on the changes made and hope for the future. When we learn about these kinds of genocides we can learn about present genocides and how to prevent them. I hope my art can show the changes made after genocide is perpetrated and inspire others to keep making changes to prevent a genocide from happening again.

As I Sit Here

By Asha Osman, Casco Bay High School Class of 2024

Written word on paper and foam board

My poem is based on the Uyghur genocide that is happening right now. Chinese authorities began arresting huge groups of Uyghur people in what they're calling “reeducation institutes,” which in reality are prison camps. They are torturing, forcing sterilization on women, and making them do things that are haram (illegal) in Islam, like eating pork. I wanted to bring light to this genocide and how I felt about it.

As a Muslim, it is really hard for me to learn about this genocide. In my poem, I wrote in all lowercase to show how I felt I couldn't do anything to help, until at the end when I felt like I could do something; I could speak out against the genocide. Simultaneously, I felt grateful but also useless for not being able to do anything about it. I was inspired to bring awareness to this genocide by learning about how people resisted the Holocaust through poetry and artworks. This made me choose to write about the Uyghur genocide, to shed light on it and how it feels to live in a day and age where people are being tortured for believing in something different from another person.

ְתקוּ ָמה tequmah [te-koo-mah]

Rebirth, Revival, Resurrection, Resistance, Recovery, Uprising

By Danielle Purington-Kane, University of Southern Maine, Class of 2022

Art resin epoxy, distressed and painted linen as the background/ uniform, thread, polymer clay, floral wire, empty bullet shells, and LED lights on copper wire

My artwork is titled tequmah, a Hebrew translation of ‘rebirth, revival, resurrection, resistance, recovery, uprising’ as a memorial to Holocaust survivors and lives lost in concentration camps, gas chambers, and mass murders by Einsatzgruppen. This piece is made up of many layers, just as all victims and survivors of genocide are humans comprised of multiple layers.

The Star of David is a symbol of Judaism. During the Holocaust, Jewish people were required to wear the Star of David to identify them, it was a badge of dehumanization. Here, the Star of David is a label of resilience and pride in a people, showcasing their faith.

A sunflower is often seen as a symbol of peace and livelihood. But sunflowers were also planted on the graves of German SS soldiers during the Holocaust, while Jewish people were thrown into mass graves or cremated in crowds. Holding the Star of David inside the Sunflower honors Jewish lives that did not receive proper burials and/or suffered inhumane deaths.

The flowers sprouting represent rebirth, as well as the recovery and healing found in survivors’ stories.

Einsatzgruppen, or Nazi mobile paramilitary death squads, moved around Europe committing mass murders of approximately 1.5 million Jewish people from 1939 - 1945. Most often, Jewish people were lined up at the edge of a ditch and shot with guns by firing squads. The bullets in my artwork represent the terror and dehumanization of mass murder victims, with a sense of uprising in the flowers stemming from the shells.

In September 1941, at Babi Yar in Kyiv, Ukraine, about 20 miles from Bucha, Ukraine, nearly 34,000 Jewish people were systematically murdered by Einsatzgruppen in just 36 hours – though the true number of casualties may never be known. Prisoners from nearby concentration camps were brought in to help dispose of the bodies.

During the Holocaust, Jewish people were herded like cattle to death and/or concentration camps, where they were worked, starved, and gassed to death. All prisoners were forced to wear uniforms, usually gray and blue striped. These camps killed a physical body, but they also killed the human spirit – double extermination. Prisoners resisted in many ways, one of which was by sewing a secret pocket inside their uniform to smuggle a pencil, paper, spoon, bread, or any number of necessities without it being seen.

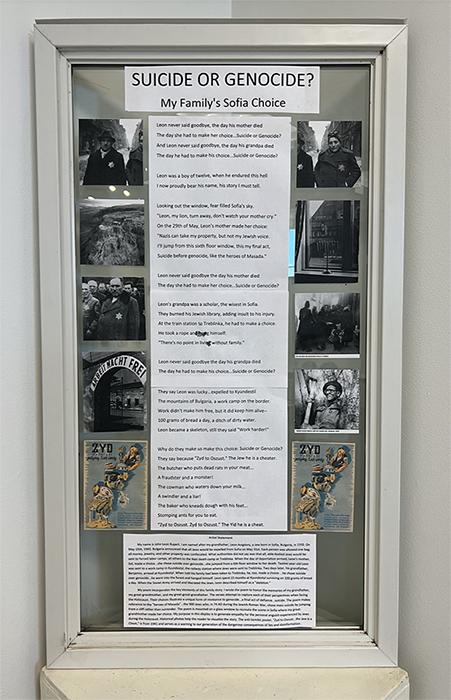

Suicide or Genocide

By John Rupert, senior at the University of Southern Maine

Windowpane, printed photographs and written word

My name is John Leon Rupert, and I was named after my grandfather Leon Avigdory who was born in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1931. In March of 1943, Bulgaria began transferring Jews to the Nazi extermination camp at Treblinka; 8,000 of whom came from Sofia. On May 15th, 1943, Bulgaria announced that all Jews would be expelled from Sofia; this included my grandfather Leon who had just turned 12. Two weeks later, when the day of deportation arrived, Leon's mother Sol chose suicide over genocide... she jumped from a window to her death. Leon was sent to a forced labor camp in Kyundestyl, the railway station where Jews expected to be sent to the Nazi death camp Treblinka. Only a few days later, Leon's grandfather, Benjamin Sarfati, arrived at Kyundestyl, and was told that his family was taken on a train to the death camps. Benjamin went into the forest and hung himself. In Kyundestyl, Leon was fed 100 grams of bread a day and water, describing himself as a "skeleton". He would spend over fifteen months there before the Soviet army entered Bulgaria and liberated the Jews.

My poem includes most of the key elements listed in the story above. I wrote this poem in order to honor the memory of my grandfather, as well as his mother and grandfather. The lines attempt to capture each of their perspectives, while they faced genocide during the Holocaust. Their stories of choosing "suicide over genocide", illustrate a less talked about form of resistance that occurred during times of genocide. The lines also incorporate my own perspective of the story and my role as the storyteller. This poem serves to memorialize the Holocaust and raise awareness concerning the persecution and genocide that Jews suffered during the Holocaust. The poem is mounted on a physical glass window in order to symbolize the window that my great grandmother jumped to her death from. Aside from including relevant historical information from the Holocaust, the poem makes reference to "the Jews of Masada", who committed a mass suicide during the first Jewish-Roman War. Historical photos taken from the WWII era are mounted along with the poem in order to help illustrate the story and make references clearer.

*The poem "Zyd Oszust" is based upon an anti-Semitic propaganda poster found in Poland in approximately 1941. While unrelated to the story of "Suicide Over Genocide", I chose to include this poem and picture to further illustrate the persecution that the Jews in Europe faced during this time.

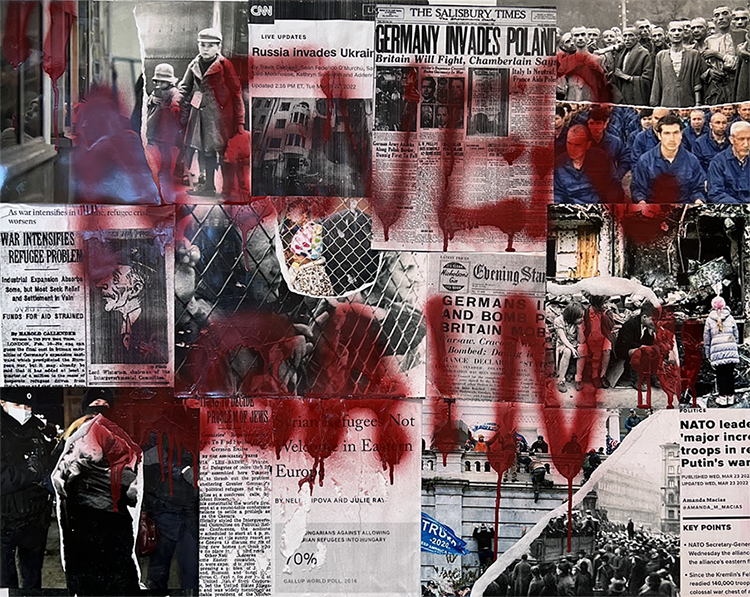

Never Again

By Meara Van Der Zee, Casco Bay High School Class of 2023

Printed photos, spray paint and Modge Podge

This piece was inspired by the course descriptor itself of Art & Genocide: A Case Study of the Holocaust: “Never again, was the cry of the world after the Holocaust …”. The world, when reflecting on tragedy, always swears they’ll never allow it to happen again. However, when it comes to this specific tragedy, warning signs echoed all over the world, even in the United States. And today, textbook signs of genocide can be found in new headlines every week.

I decided to make my piece an act of protest against empty “never again” rhetoric, when world leaders repeatedly allow these things to happen over and over again. The media I decided to use was collage, so I could force the viewer to see the undoctored photographs of these tragedies as opposed to an artistic rendition where I may not have been able to do it justice. Photos of current or recent events are torn away to reveal Holocaust era parallels, collaged with news articles from both the 1940s and recent years. The piece is then spray painted over with the words “Never Again” in red spray paint, dripping down to give the illusion of blood. The painting is intentionally on a larger canvas to make the photos visible and eye-catching.

While making this piece and researching parallels to create the collage, Putin invaded Ukraine. It scared the world, but as we studied Hitler’s invasions in the beginning of World War II, I felt it should be a focal point of the piece. Several of the collaged photographs are from the Russia/Ukraine conflict - the elderly woman being dragged away by police is torn between a photograph of a woman of similar age doing the same thing during the Holocaust. There are two photographs of children standing and sitting in the rubble of their bombed cities - one photograph of WWII London, the other in Ukraine. Several of the news articles are also about the invasion of Ukraine. However, there’s also a collage of the concentration camps in China, mixed with a photo of Holocaust victims, and a split photo of the January 6th insurrection and Beer Hall Putsch, highlighting how even a failed coup can be symbolic of the horror of many people blindly following one man, to the point where they were willing to overtake their government to please him.

“Never again” is a sentiment that rings in our ears after every tragedy - yet when it really is happening again, our governments and officials do nothing to prevent it from escalating. They commission Holocaust memorials and sell merchandise for a profit but won’t intervene when Uyghur Muslims are being murdered in camps for their religion just as Jews were in WWII. This piece was made to inspire thought about empty promises, and how the world we live in may not have progressed as far as we are led to believe.

FACELESS

By Kaethe Marie Wilson, Casco Bay High School Class of 2022

Drawing pencils and acrylic on canvas

My art piece, “FACELESS” is a depiction of the mass generalization of Jewish people during the Holocaust. The Holocaust was a mass murder of the European Jewish people committed by the Nazis during WWII. An estimated 6 million Jews died in concentration and labor camps from 1941 to 1945, when the last of the camps was liberated by the allies at the end of WWII. The Star of David behind the person as well as on their chest is the identification of someone who is considered lesser than the German peoples.

It not only represents hate towards another culture, but it also represents the erasing of a person's identity as an individual, not just someone who is a part of a certain race or religion. The person remains faceless as they do not have an identity other than being a Jew. I took inspiration from Simon Wiesenthal’s book The Sunflower, in the scene where Wiesenthal comes face to face with a dying Nazi called Karl, who asks him for forgiveness for his sins so he may die in peace and go to heaven. Through Wiesenthal, Karl is asking for forgiveness from all Jews for his atrocities to the people. In this action he is not only putting the death of hundreds of people in Wiesenthal's hands, but he is minimizing the Jewish people he has killed by foisting the responsibility onto one person who was not even there and has no relation to the people he has killed other than he is a person of the Jewish faith. With this work of art, I hope to bring awareness to the reductionism of Jewish people and those who follow the Jewish faith throughout WWII.

Exhibit Introduction

Leslie Appelbaum and Matt Bernstein, teachers at Casco Bay High School, learned by informally speaking with students that they were no longer studying The Holocaust. Alarmed, they researched and found that Holocaust education was, indeed, on the decline worldwide at the precise time that bigotry and hate speech were on the rise. They are firm believers that education alone can render students feeling helpless. Rather than enshrine knowledge, Applebaum and Bernstein wanted students to see how art had been and continues to be a tool of peaceful empowerment.

So these teachers developed a university course to inform students about the Holocaust, how it happened and how it was allowed to happen. They wanted students to understand both the participants (active and passive) and the heroic efforts of those fighting against it. Secondly, they wanted to weave in artists—focusing on two- and three-dimensional visual artists and poets—to illustrate how individuals at the time protested war and the Holocaust, to show how artists created powerful forms of activism as a way of contributing to the solution.

The Reflections on Genocide exhibit derives from a collaboration between Casco Bay High School and the University of Southern Maine, where students expressed their reflections on the university course “Art and Genocide: A Case Study of the Holocaust” through art as activism.

The art encompasses memorials to relatives designed to put a face on this genocide and attacks against members of any community. The art serves as a historical reminder so we may never forget. At times, the art conveys a sense of loss, an awareness of what disappears when we, as a collective, are at our worst. At other times, the art expresses how audacious hope is—as seen through abstract art that makes concrete the intangible. The students’ work poignantly evokes the horror in every act of genocide and, equally powerfully, the forces that fight against the hatred with love.

Interactive Wall

An interactive wall offers an opportunity for people to engage personally with the art they have just experienced. The description suggests that in your community, bravery goes both ways: it involves giving and receiving. This means taking a risk to say something that is difficult or scary. It is also brave to listen fully and hear hard things that people may tell you. A brave space is one in which you accept that you will feel uncomfortable and maybe defensive when exploring issues of bias, injustice, and oppression but take risks with care and compassion to nurture a sense of belonging. Share your ideas on how to create a brave community using images or word. Some possible questions to think about: "How am I connecting with what I have seen here today? What hope sparked in me? What would I need to feel a greater sense of belonging in my community? How can I better welcome a person who is different than me in my community? What act feels like it takes courage, but I have been meaning to do?"