Juneteenth

By Sara Lennon

Juneteenth, now a federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans, is celebrated on the anniversary of June 19, 1865 when Major General Gordon Granger read the proclamation of freedom for slaves in Galveston, Texas. General Order Number 3 began most significantly with: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, promising freedom to the slaves in the rebellious parts of Southern secessionist states of the Confederacy, but not in federally held territories such as Delaware , Maryland, and West Virginia. It took over two years for the law to make its way across the country as enforcement relied on the advance of Union troops. When emancipation finally came to Texas, the last state to hear the official news as the southern rebellion collapsed, celebration was widespread. While that date didn’t mark the unequivocal end of slavery, June 19 became a day of celebration across the United States—created, preserved, and spread by African Americans.

Writes Kelly E. Navies, Museum Specialist of Oral History for the National Museum of African American History & Culture, “I like to think of Juneteenth as a celebration of freedom, of family, and of joy that emerged from this cauldron of the war. After hundreds of years of enslavement, and the intense post-Civil War era, all of these emotions and feelings had built up to a particular point. Then, General Granger arrives with his troops (some of whom were members of the United States Colored troops) to announce that they will enforce the Emancipation Proclamation.” Read more from the museum curators.

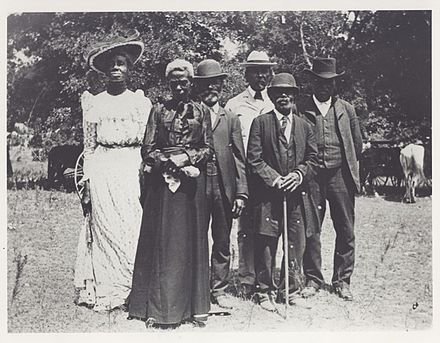

In the early years, it was almost exclusively African American communities that participated in the day’s celebrations, often in rural areas to avoid disruptions. Rivers and creeks offered fishing, horseback riding, games and back yards or church grounds hosted many barbecues. Juneteenth also focused on education, self improvement, and prayer services—plus feasting on red strawberry soda, barbecued meats, and special dishes for the occasion. The emphasis was on family, community, celebration and remembering.

When African Americans began to own land, it was donated and dedicated for these festivities. One of the earliest documented land purchases in the name of Juneteenth was organized by Rev. Jack Yates, who raised $1,000 to purchase Emancipation Park in Houston, still popular today and a favorite place for Juneteenth gatherings. In Mexia, the local Juneteenth organization purchased Booker T. Washington Park in Virginia, which has been a place for Juneteenth celebration site in 1898. Read more about its history at Juneteenth.com.

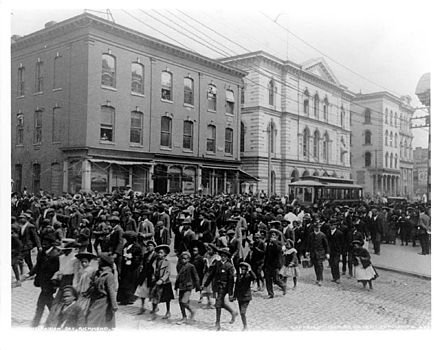

For decades the holiday celebrations were almost exclusively for and among African Americans, in towns and communities scattered across the south. But it grew in popularity after the Great Depression. In 1936, an estimated 175,000 people joined the holiday’s celebration in Dallas. 70,000 attended a “Juneteenth Jamboree” in 1951. In 1945, Juneteenth was introduced in San Francisco by a migrant from Texas, Wesley Johnson. From 1940 through 1970, in the second wave of the Great Migration, more than five million black people left Texas, Louisiana and other parts of the South for the North and the West Coast. As historian Isabel Wilkerson writes, “The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went.” During the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement focused the attention of African Americans on expanding freedom and integrating. As a result, observations of the holiday declined again, though it was still celebrated in Texas. In the late 1970s, the Texas Legislature declared Juneteenth a “holiday of significance…particularly to the blacks of Texas,” and establish Juneteenth as a state holiday. Before 2,000, three more U.S. states officially observed the day, and over the next two decades it was recognized as an official observance in all states except South Dakota, until it was declared a federal holiday by President Joe Biden in June 2021. Read an essay by Annette Gordon-Reed "Growing Up with Juneteenth” published in The New Yorker on June 19, 2020.

Like all holidays, Juneteenth responds to cultural, political, and major events in the nation. It has waxed and waned in popularity over its 156 year history. What began as small and local, grew as migration carried the traditions out of the south. Urban areas saw celebrations in parks; states gradually began to codify it into a holiday. Over time, others joined to commemorate, and the celebrations spread. Writes Brianna Holt, a culture writer and editor at The New York Times, “The entire celebration lasted only six hours but had the vitality to keep you feeling warm and loved throughout the summer. It acted as a reminder that there was a community of people who were rooting for you, supported you and wanted to see you succeed. Every time you left a Juneteenth celebration, you took with you new stories, new connections and a new sense of what it meant to be black, but specifically what it meant to be black in Texas. Her essay from 2020 considers the celebrations of her childhood, the evolution of its significance and importance, and how it feels to in the wake of nationwide protests over the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. “Whatever might come, I know where I’ll be on Friday: celebrating the continued fight that the brave and relentless people before me expect for my generation to carry on. Read Brianna Holt’s essay.

The Juneteenth flag is a symbol for the Juneteenth holiday in the United States. The first version was created in 1997 by activist Ben Haith and the present version was first flown in 2000. The flag uses the colors of red, white and blue from the American flag. Featured prominently in the center of the flag is a bursting star. Running through the center of the flag horizontally, is an arc that is meant to symbolize the new horizon of opportunity for black people. The red, white, and blue convey that all enslaved people and their descendants are American. The date marks General Order No. 3 issued in Galveston, Texas in 1865. Many states began recognizing Juneteenth by flying the flag over their state capitol buildings, especially after it became a federal holiday on June 17, 2021. Read more about the Juneteenth flag on Parade.com.